The term “no-kill” isn’t about refusing to euthanize; it’s an operational strategy to manage animal intake and prevent the entire system from collapsing under the weight of overcrowding.

- Limited or “managed” admission is the primary tool used to ensure the quality of care doesn’t fall below humane standards.

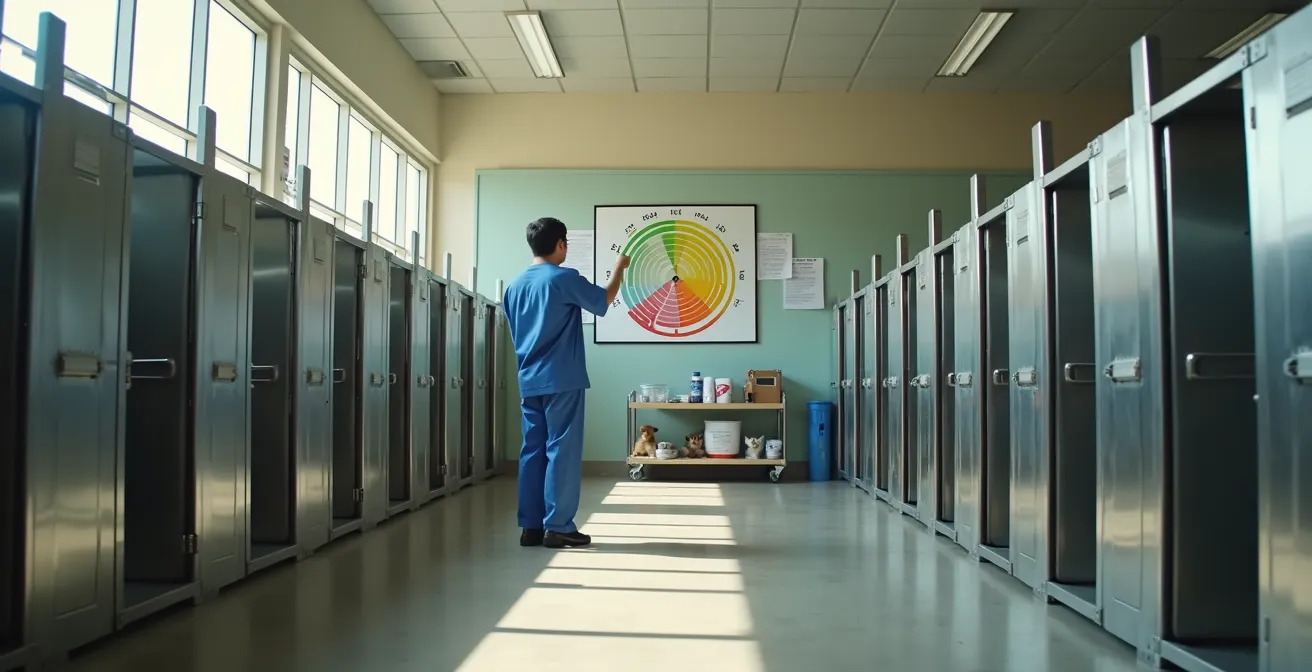

- “Capacity for Care” (C4C) is the guiding metric, focusing on the quality of life for each animal, not just the number of available kennels.

- Community-based programs like Trap-Neuter-Return (TNR) and robust foster networks are critical to reducing the pressure on shelter intake.

Recommendation: Support shelters by understanding their specific admission policies—whether open or limited—and volunteering for roles that directly alleviate their unique operational bottlenecks.

The term “no-kill” evokes a powerful, hopeful image: a safe haven where every animal is guaranteed a chance at life. As a potential donor or adopter, you’re drawn to this promise, believing it represents the highest standard of compassion. You might see stories of shelters clearing their kennels through mass adoption events or heroic foster networks and assume this is the entire picture. This narrative, while heartwarming, often obscures the complex and sometimes heartbreaking operational reality required to maintain that status.

From my perspective as a shelter operations director, the daily challenge isn’t just finding homes; it’s a constant, high-stakes balancing act. The public conversation focuses on outputs—adoptions and save rates. But the real, unseen work happens on the input side. The truth is, managing overcrowding in a no-kill environment isn’t magic. It’s a calculated, data-driven strategy of resource management, biosecurity protocols, and, most controversially, controlled intake.

But if the core of the strategy is not simply an open door, what does that mean for the animals left outside? This article peels back the curtain on the operational mechanics of the no-kill movement. Instead of focusing on the label, we will explore the system itself. We will unpack the difficult concept of “Capacity for Care,” reveal why you might be turned away when trying to surrender an animal, and explain the crucial difference between a municipal pound and a private rescue. This is the transparent look inside that explains how we prevent the promise of “no-kill” from leading to a collapse in humane care.

To add a challenging but essential perspective to this discussion, the following video explores the nuances and difficult ethics behind different shelter philosophies. It provides a valuable counterpoint that enriches the understanding of the entire animal welfare ecosystem.

To fully grasp the intricate system that keeps shelters functioning, this guide breaks down the core operational components. The following summary outlines each critical aspect we will explore, from intake policies and volunteer strategies to the science behind disease prevention and successful adoption marketing.

Summary: Unpacking the “No-Kill” Operational Playbook

- Why limited admission shelters must turn away animals to maintain care standards?

- How to volunteer at a shelter if you are emotionally sensitive to suffering?

- Municipal Pound vs Private Rescue: Which receives taxpayer funding for care?

- The Parvo Protocol: Why you can’t touch puppies during your first shelter visit?

- How to write a bio for a “boring” black dog to get him adopted in 48 hours?

- Why removing strays without sterilization just invites new cats to move in?

- Why fostering is about “goodbye” and not “keeping”: The mindset shift?

- How to Choose a Rescue Dog That Actually Fits Your Lifestyle Reality?

Why limited admission shelters must turn away animals to maintain care standards?

The most misunderstood aspect of the “no-kill” model is the concept of limited admission. It seems counterintuitive: how can you save lives by turning animals away? The answer lies in a professional framework called “Capacity for Care” (C4C). This isn’t just about having an empty kennel; it’s about having the staff, time, medical budget, and enrichment resources to provide a humane quality of life for every single animal in the building. When a shelter exceeds its C4C, stress levels skyrocket, disease spreads rapidly, and staff become overwhelmed, leading to a catastrophic decline in welfare for all.

A limited admission policy, also known as “managed intake,” is a proactive strategy to prevent this collapse. Instead of accepting every animal surrendered at the door, the shelter schedules intakes based on its current capacity. This might mean placing owners on a waitlist and providing them with resources—like pet food or behavioral advice—to help them keep their pet in the meantime. The goal is to make surrender a last resort, not the first option. This operational shift has profound effects. In West Virginia, Harrison County Animal Control implemented managed intake and saw their save rate jump from 45% to 83% in a single year, all while intake dropped by 400 pets, as highlighted in a report from Best Friends Animal Society.

By managing the flow of animals coming in, shelters can dedicate adequate resources to the animals already in their care, making them more adoptable and moving them out faster. This focus on quality over quantity is proven to work. Implementing the C4C model leads to a 15% average increase in adoption probability for cats, demonstrating that controlling intake directly improves lifesaving outcomes. It’s a difficult choice, but it’s the choice that allows a shelter to fulfill its promise of life, not just warehousing.

How to volunteer at a shelter if you are emotionally sensitive to suffering?

The desire to help animals is strong, but for many emotionally sensitive people, the thought of walking through kennels filled with lonely or suffering animals is a significant barrier. The noise, the sadness, and the sheer scale of the need can be overwhelming. As a director, I see well-meaning individuals burn out quickly from this direct exposure. This phenomenon is so common it has a name: compassion fatigue. It’s a state of emotional and physical exhaustion that can lead to a decreased capacity to empathize.

As expert Jessica Dolce notes in the context of her work with the University of Florida, this is a pervasive issue. In a discussion about her compassion fatigue course, she states:

I have recommend it to everyone in my organization, knowing that all shelter workers, from kennel staff to adoption counselors, are at risk for compassion fatigue.

– Jessica Dolce, University of Florida Compassion Fatigue Strategies Course

However, the most critical work in a shelter often happens far from the kennel floor. A modern shelter is a complex non-profit organization with needs in marketing, data analysis, fundraising, and administration. You can leverage your professional skills to save lives without ever having to handle an animal directly. These roles are not “lesser” volunteer positions; they are the engine that powers the entire lifesaving operation, providing the resources and insights needed to care for and adopt out animals.

These indirect roles protect your emotional well-being while providing immense value. By focusing on the operational side, you become a crucial part of the machinery of hope, ensuring that the front-line caregivers have the support they need to do their jobs effectively. Below is a checklist of high-impact roles you can perform, often from the comfort of your own home.

Action plan: High-impact, non-animal-facing volunteer roles

- Grant writing: Research and write funding applications to secure resources for medical care and shelter programs.

- Data analysis: Track adoption outcomes and identify trends to improve shelter operations and marketing strategies.

- Social media management: Create compelling content and manage online profiles to promote adoptable animals from home.

- Transport coordination: Organize animal transfers to partner rescues, handling logistics and paperwork without direct animal handling.

- Foster support hotline: Provide phone or email guidance to foster families, offering support and advice from a distance.

Municipal Pound vs Private Rescue: Which receives taxpayer funding for care?

The terms “shelter,” “pound,” and “rescue” are often used interchangeably, but they represent fundamentally different entities with distinct obligations and funding models. Understanding this difference is crucial for any donor or volunteer. The key distinction lies in their admission policy and their source of revenue. A municipal shelter, often called a “pound” or “animal control,” is a government entity. Its primary responsibility is public safety and animal control, which means it operates under an open admission policy. It is legally obligated to accept every stray, abandoned, or surrendered animal from its jurisdiction, regardless of health, temperament, or available space.

Because of this legal mandate, municipal shelters are primarily funded by taxpayer dollars. They are accountable to the public and must handle the entire scope of a community’s animal problems, from roaming dog complaints to cruelty case seizures. This relentless inflow of animals, many of whom may be unadoptable due to severe medical or behavioral issues, is why these facilities have historically had higher euthanasia rates. They are forced to make life-or-death decisions based on limited space and resources.

In contrast, a private rescue is typically a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization funded almost entirely by private donations, adoption fees, and grants. They are not beholden to government contracts (though some may contract to provide pound services) and can therefore operate a limited admission policy. They can choose which animals to accept, often pulling “adoptable” animals from overcrowded municipal shelters. This selective intake is the primary reason they can often maintain a “no-kill” status. The following table breaks down these core differences.

This side-by-side comparison highlights the different pressures and operational models. The data reveals that while progress is being made, the system is a patchwork of different capabilities, with a recent report showing that 52% of 4,110 shelters are no-kill, indicating a nearly even split in operational philosophies nationwide.

| Aspect | Municipal Shelters | Private Rescues |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Funding | Taxpayer dollars | Donations & grants |

| Admission Policy | Open admission (must accept all) | Limited admission (can refuse) |

| Government Contracts | Direct operation | May contract as municipal pound |

| Euthanasia Decisions | Based on space/resources | Typically avoid via selective intake |

| Public Accountability | Required reporting | Voluntary transparency |

The Parvo Protocol: Why you can’t touch puppies during your first shelter visit?

Walking into a shelter and being told you can’t cuddle the puppies can feel cold and unwelcoming. It’s a common point of frustration for potential adopters. But this rule isn’t about being difficult; it’s a critical component of a shelter’s biosecurity defense system against one of its deadliest enemies: Canine Parvovirus. Parvo is an extremely hardy and highly contagious virus that attacks the gastrointestinal tract of puppies and young dogs. It is incredibly lethal, and an outbreak can wipe out an entire litter in days, forcing a shelter into a costly and demoralizing quarantine.

The virus spreads through contact with infected feces, but it can live on surfaces for months. This is where the concept of fomites becomes critical. A fomite is any object—your shoes, your hands, your clothing—that can carry an infectious agent. If you’ve recently been to a park, a pet store, or even walked on a sidewalk where an infected dog has been, you could be an unknowing carrier. By restricting access to vulnerable puppy populations, shelters are creating a firewall against a threat you can’t see. Regular household cleaners are useless against it; specialized virucidal products are required to decontaminate an area.

The effectiveness of these strict protocols is not theoretical. Research from the UC Davis Koret Shelter Medicine Program, a leader in the field, provides clear evidence. A study on their C4C model found that implementing proper biosecurity protocols, including restricted puppy access for new visitors and meticulous cleaning procedures, helped reduce infectious disease isolation rates by 56% across participating shelters. These protocols include chemical footbaths, a strict order for cleaning kennels (puppies first, then healthy adults, then isolation), and preventing the public from becoming accidental vectors. So, when a volunteer asks you to use hand sanitizer and step back from the puppy kennel, they’re not just protecting that puppy; they’re protecting every vulnerable animal in the building.

How to write a bio for a “boring” black dog to get him adopted in 48 hours?

“Black dog syndrome” is a well-documented phenomenon in shelters. Large, dark-colored dogs are consistently the last to be adopted. They don’t photograph well, their facial expressions can be hard to read in a dim kennel, and they often blend into the shadows. Their bios often reflect this, falling back on generic phrases like “loyal companion” or “loves to play.” From an operational standpoint, a dog that sits in a kennel for months is a drain on resources and C4C. The key to moving these “boring” dogs is to stop describing what they look like and start marketing the experience of owning them.

Instead of “medium-sized black mix,” write “The perfect Netflix-and-chill partner who rests his head on your lap but will never steal the remote.” Instead of “needs a yard,” try “Your weekend hiking captain, ready to conquer every trail and then collapse in a happy heap at your feet.” The goal is to paint a vivid picture in the adopter’s mind, allowing them to imagine the dog in their own life. Use humor, specific quirks, and sensory details. Does he snore? Does he greet you with a specific toy? Does he love the smell of bacon on a Sunday morning? Those are the details that create connection, not coat color.

This personality-driven approach was famously demonstrated by YouTube star MrBeast, who visited the Furkids shelter with a mission to get every animal adopted. His team didn’t just take photos; they created engaging, story-driven content for each animal, focusing on their unique personalities and quirks.

YouTube star MrBeast helped Furkids Dog Shelter achieve unprecedented adoption success by creating engaging, personality-driven content for each dog. His team spent three days filming, focusing on each dog’s unique quirks rather than generic descriptions. The video approach emphasized the adopter’s future experience with the pet, resulting in clearing the entire shelter.

You don’t need a YouTube star to apply this principle. You need an observant volunteer or staff member to spend 15 minutes with the dog outside its kennel and write down three unique things about them. That’s the raw material for a bio that sells an experience, not just a dog, and can turn a long-term resident into an overnight adoption success.

Why removing strays without sterilization just invites new cats to move in?

For decades, the standard response to a colony of stray or feral cats was to trap and remove them, often leading to their euthanasia at a municipal pound. While this seems like a straightforward solution, ecologists and shelter professionals have long known it is deeply ineffective. This approach creates a phenomenon known as the “vacuum effect.” A cat colony exists in a specific location because there is a source of food and shelter. When the existing cats are removed, this resource-rich territory is left open, creating a “vacuum” that quickly pulls in new, unsterilized cats from surrounding areas. The cycle of breeding and nuisance complaints begins all over again.

The modern, effective, and humane alternative is Trap-Neuter-Return (TNR), sometimes called Trap-Neuter-Vaccinate-Return (TNVR). In a TNR program, community cats are humanely trapped, transported to a clinic, spayed or neutered, vaccinated against rabies, and “eartipped” (a small, painless snip on the top of one ear to signify they are sterilized). They are then returned to their original territory. They can no longer reproduce, so the colony size gradually diminishes through natural attrition. The stabilized, non-breeding colony also acts as a placeholder, defending its territory and preventing new, fertile cats from moving in.

This strategy is not just kinder; it is a fiscally and operationally superior way to manage community cat populations. It dramatically reduces the number of kittens flooding shelters during “kitten season.” For example, a successful program at the Fairfax County Animal Shelter demonstrated a 41% reduction in kitten intake over a three-year period after implementing a robust TNR program. Furthermore, as shown by The Animal Foundation’s work, a community-focused approach can be scaled effectively. In 2024, they expanded their programs and returned over 800 more cats to their outdoor homes than the prior year, using humane deterrents like motion-activated sprinklers to address neighbor concerns while stabilizing the colonies.

Why fostering is about “goodbye” and not “keeping”: The mindset shift?

Foster homes are the lifeblood of any successful rescue organization. They provide a quiet, low-stress environment for animals to recover from illness, decompress from shelter life, or simply grow big enough for spay/neuter surgery. Yet, the single biggest hesitation I hear from potential fosters is, “I could never say goodbye. I’d get too attached.” This fear, while understandable, stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of the foster role. Fostering is not a trial adoption; it is a temporary, mission-driven volunteer position. The goal is not to get a pet; the goal is to save a life by preparing an animal for its forever home.

The necessary mindset shift is to see yourself as a bridge, not a destination. You are a vital stepping stone on an animal’s journey from a precarious situation to a loving, permanent family. Your role is to provide the care, socialization, and love that makes them adoptable. The “goodbye” is not a moment of loss; it is the moment of mission success. It’s the graduation. This perspective is championed by experts like Hannah Shaw, the “Kitten Lady,” who has fostered hundreds of neonatal kittens.

Despite everything she goes through with her rescues, Shaw insists it’s not hard to say goodbye when the kittens get adopted.

– Hannah Shaw (Kitten Lady), NPR Interview on Fostering

To help volunteers navigate this emotional journey, progressive shelters are implementing foster mentorship programs. These programs are designed to celebrate the “goodbye” and build a supportive community. They reframe the end of a foster period as a victory to be shared, not a loss to be mourned alone. Key components often include:

- Pairing new fosters with experienced veterans for emotional support during the first goodbye.

- Holding “graduation ceremonies” or parties to celebrate successful adoptions.

- Creating foster alumni photo walls or online groups showing fostered animals thriving in their forever homes.

- Implementing a 24-hour foster support hotline for moments of crisis or doubt.

- Rotating foster assignments to prevent over-attachment to a specific animal or type of case.

By embracing the “goodbye” as the ultimate goal, you can transform a moment of potential sadness into one of profound accomplishment. Each animal you foster and say goodbye to opens up a space in your home—and in the shelter—to save another life.

Key Takeaways

- “No-kill” is an operational model based on managed intake and resource allocation, not a promise of unlimited space.

- Capacity for Care (C4C) is the guiding metric that prioritizes the quality of life and health for every animal over sheer numbers.

- Community programs like TNR, foster networks, and owner support are as vital to lifesaving as adoptions, as they reduce the strain on shelter intake.

How to Choose a Rescue Dog That Actually Fits Your Lifestyle Reality?

You’ve done your research, you understand the system, and you’re ready to adopt. The final, critical step is to choose a dog that genuinely aligns with your real life, not your fantasy life. Many adoptions fail because of a mismatch between the adopter’s expectations and the dog’s needs. You might love the idea of a high-energy Border Collie, but if you’re a homebody who works 10-hour days, that’s a recipe for a frustrated, destructive dog and a miserable owner. Honest self-assessment is the most important part of the adoption process.

Forget about breed, color, or a sad story. Focus on two things: energy level and temperament. Is your home a quiet, calm sanctuary or a bustling hub of activity with kids and visitors? Are you looking for a weekend adventure buddy or a couch potato? Be brutally honest with the adoption counselor. Their job is not to “sell” you a dog; it’s to make a lasting match. A good counselor will ask probing questions about your daily routine, your experience with dogs, and what you’re truly looking for in a companion. Trust their judgment—they have spent weeks, if not months, getting to know these animals’ true personalities outside of the stressful kennel environment.

Shelters are also improving how they present animals to facilitate better matches. Simple operational changes can make a huge difference in an adopter’s ability to see an animal’s true self. For instance, the Milwaukee Area Domestic Animal Control Commission (MADACC) saw a 54% increase in cat adoptions simply by moving cats to a dedicated room away from the noisy lobby and adding daily enrichment. These calmer environments help potential adopters assess personality more accurately. Ultimately, the success of the no-kill movement, which has seen the national save rate reach a benchmark of 82%, depends on these successful, permanent matches. Choosing the right dog is the final, crucial piece of the lifesaving puzzle.

Armed with this knowledge, your next step is to engage with your local shelter not just as a potential adopter, but as an informed advocate. Ask them about their admission policy, their C4C model, and what volunteer roles they need most, and become part of the solution.

Frequently Asked Questions About Shelter Operations

What are fomites and why do they matter in shelters?

Fomites are objects or materials (clothing, hands, shoes) that can harbor infectious agents. Parvo virus can survive on fomites for months, making them deadly disease vectors in shelter environments. This is why staff are so strict about hand washing and controlling traffic in puppy areas.

How much can a parvo outbreak cost a shelter?

A single parvo outbreak can cost tens of thousands of dollars in treatment, require weeks of quarantine that shut down adoptions entirely, and devastate a shelter’s morale and save rate statistics. The cost is not just financial; it’s emotional and operational.

What cleaning products actually kill parvo?

Specialized products like Rescue (Accelerated Hydrogen Peroxide) or commercial-grade bleach solutions are required. Regular household cleaners are ineffective against this extremely resistant virus, which is why shelters follow strict, professionally developed cleaning protocols.